My Pet Claude

The economics of agentic software development

I am eager, in fact desperate, to write a post that has nothing to do with AI. Next week I will produce a 5,000 word essay on the history of sawmills in rural Nebraska or the breeding patterns of giant tortoises. Yet no matter how hard I tried to research the agricultural history of the Midwest,1 my mind kept returning to Claude.

Concerning My Addiction to Vibes

I avoided spending too much time with existing SDD or orchestration libraries ahead of last week’s post. This strategy appears to have worked for Stephenie Meyer, so why not me? Since then I’ve played with several popular repositories—by and large, I’ve been disappointed.

Everyone is grasping toward the same concepts. But so many of these libraries feel like a given developer’s personal preferences vibe-coded into an arbitrary and poorly documented new interface. Spec-kit is basically a templating engine for PRDs, yet has managed to accumulate 60,000 stars on GitHub? I suppose this could be nice for anyone who has never had to write a Jira story in their life… but for an experienced developer, why bother? OpenSpec and BMAD are similar. It’s the engineering equivalent of automating an Atlassian how-to guide. If you need the convenience methods, just write a custom Claude command to draft with your preferred template.

I feel similarly about beads and gas town. I only recently set up gas town on an EC2 instance (my personal Nevada test site), so I’ll withhold from commenting on its efficacy, aside from the popular remark that the documentation is bizarre. I assumed beads could be applied more easily to my existing workflow, but in practice felt again like an individual’s convoluted, idiosyncratic workflow being hoisted into a library to replace… what? A ticketing system? I am often worried that software engineers, when given superpowers and the freedom to change the world, would only choose to rewrite the entire Atlassian suite according to their personal quirks.

From a research perspective, it’s valuable to explore and build in this direction, but for production use I would approach new tools and workflows with significant skepticism. Ultimately, Anthropic is in the best position to make any new SDD or orchestration workflows effective, by building them into Claude Code itself. Over the past week, we have already seen the release of tasks, which are directly influenced by beads, and have already received early reports of new swarm, delegation and team coordination features. Should we spend cycles building more orchestration libraries when native support is just around the corner?

Despite my specific advice to wait for orchestration features, it remains very difficult to calibrate when to build your own tooling, when to leverage libraries and when to wait for native capabilities. I still spent a recent afternoon setting up an EC2 sandbox for gas town and other High Risk Activities, instead of using sprite.dev or an equivalent service. And since I disliked beads and have yet to see the benefits of Claude’s new task system, I decided to write my own simple ticketing system (take that, Jira). The cost of producing software is now so low that small frictions in developer experience or minor SaaS fee considerations are enough to justify a couple hours of agentic development. Tooling at the frontier is inherently imperfect, so the marginal cost of writing your own software may be less than the cost of understanding a new solution.

Putting Claude to Work: Labor and Capital Allocation

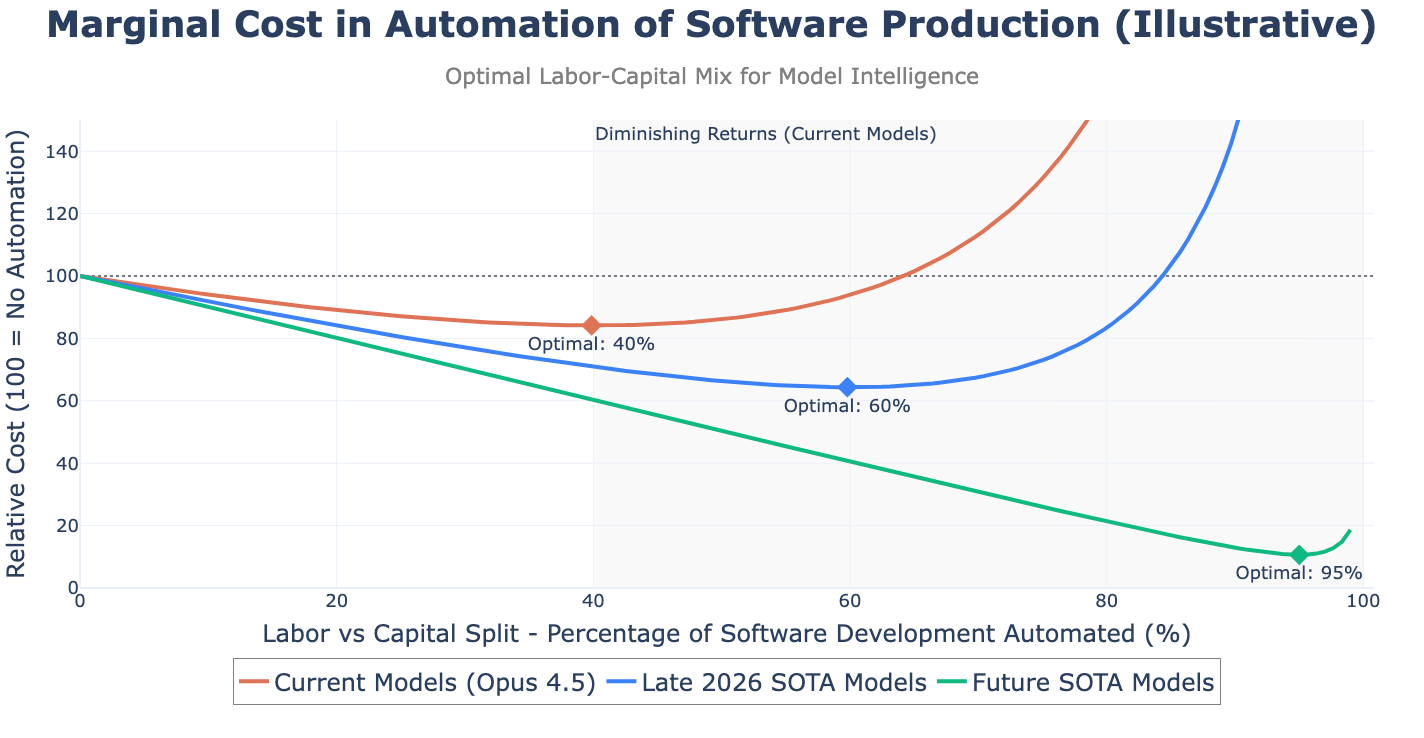

Beyond an inflection point, the marginal cost of further automating software production actually increases, and is eventually infeasible at current levels of model intelligence.

When building a factory, planners must decide on the optimal ratio of labor (people) to capital (machines) for production. Even if technically possible to fully automate production, the marginal cost of fully automating production is so high that it is remains more efficient to only partially automate production, retaining labor for activities where humans hold a comparative advantage over machines. This concept may be counterintuitive for engineers that have a drive to automate as many tasks as possible.

We can apply the same framework of labor-capital splits to software production. Here, labor refers to the activities of all people involved producing software, most notably software engineers. I’ll use capital to mean any non-labor asset used in the production of software. For simplicity’s sake I won’t distinguish between a company’s own capital assets and the assets they rent. So I consider Claude Code capital, though it would appear as an operating expense on a balance sheet, not a capital investment.

Software development is traditionally a labor intensive activity, even if the output of development, software, is a capital asset that can be leveraged across a huge consumer base. Producing software has long involved teams of product managers, quality assurance testers, support agents, designers and, of course, programmers. That is not to say that the labor mix in software production has been static, or that software development has not become more efficient over time. The past decades saw increasing levels of automation for software operations, mostly thanks to the advent of cloud computing and the associated DevOps and SRE practices, which eliminated/reduced many traditional IT and ops positions (like database administrators). Yet labor has remained essential for the actual production of software.

Just as the mechanical loom in the Industrial Revolution shifted production away from textile workers, Claude Code in the AI revolution allows us to shift software production from labor (programmers and the rest) to capital (rented or otherwise).

Epochal shifts in modes of production do not complete overnight. Capital and labor are not binaries, but a ratio that a company must effectively calibrate to optimize their balance sheet. Considering the automation of software operations, the cloud did not immediately eliminate traditional servers.2 Advances in virtual machines and containerization slowly spread throughout the software community, while new roles and practices gradually evolved to capitalize3 on those changes. Even today, when serverless technology is broadly adopted, we have not unified around a single kind of compute or storage layer, but make tradeoffs in how thoroughly we choose to adopt serverless abstractions. We should consider agentic development in the same light—not as a binary, but as a series tradeoffs as to the degree of automation desirable.

So what is the optimal degree of software automation today? I argue that the optimal labor-capital split is a function of model intelligence, where intelligence is a catch-all term for reasoning, instruction compliance, etc. Beyond this ratio, there are no marginal gains in efficiency, and companies will experience diminishing returns on further automation of software production. Here’s an illustrative chart of the phenomenon.

Remember that “software production” refers to the entire set of activities necessary to produce software, not just writing code.

Please don’t anchor too hard on the specific numbers I’ve proposed, which are more vibes than rigour. I’ve calibrated my guess on the Stanford study citing productivity gains of around 10 - 40% depending on the complexity of the task (the study precedes the latest coding models). The initial productivity gains of agentic coding are strong (consider the automation of rote activities and greenfield projects), but tapers off into a wide trough of mildly differentiated gains. This is where many software developers are spending their time today, experimenting with different agentic coding strategies. The marginal costs are similar in the region around the optimum, so there is only a small penalty for automating a little too far. But further on the costs increase asymptotically—you will hit a wall if you try to automate your entire workflow.

Today’s models are great at one-shotting discrete tasks, but still fall over when faced with complexity and expanding requirements. It is well understood that filling the context window rapidly reduces the quality of current models. But, in the context of software development, I would add that even minor, seemingly harmless deviations from instructions and design principles cascade into core technical problems. I naively reason about this as an issue of compounding errors. Suppose Claude Code is 5% “off” expectations for every changeset, meaning it very slightly deviates from requirements or design principles. Without manual feedback or review, Claude will continue to deviate your codebase by 5% for every subsequent change. After 5 iterations you would then have deviated 28% from expectations; after 10 iterations, you would be 62% off. In practice error rates probably do not compound so neatly, but it’s true that without human supervision vibe-coding comes to halt under the weight of its own technical debt. Agentic coding continually adds entropy to the codebase. So small gains in adherence and reasoning can have massive gains in the number of change sets feasible without human intervention.

The relative cost of automating software production is sensitive to the fees charged by Anthropic and its competitors. We are all the beneficiaries of a competitive market with large subsidies. I did not find any public numbers confirming the “true costs” of a typical Claude Max plan, or any company’s real per-token cost for a SOTA reasoning model. We do have reports that in 2025 Anthropic suffered a $5.2 billion loss against $9 billion in ARR, while OpenAI expected to spend $22 billion against $13 billion in sales. With those losses it seems reasonable to expect that “real costs” for Claude Code users are at least 2x what we pay, though if we further assume that a small percentage of Claude Code users consume the vast majority of tokens, then it’s likely the real costs for Claude Code users are much greater. However, I’d guess there are few hard technical limits on optimizing the inference layer of any given model, so it’s likely Anthropic and competitors could engineer away some of the cost problems if they were compelled to chase profitability. When making critical budget and staffing decisions, engineers and business leaders would be prudent to just keep in mind these costs might increase someday to better reflect real costs.

I’ve charted the labor-capital split relative to a pre-AI baseline of current software output (say, late 2023). The bull case for the labor market is that overall software output will grow apace with the new efficiencies. The low cost of software production creates competitive pressure to add new feature, develop new products, and automate increasing amounts of the economy. So even if fewer software engineers are needed relative to overall software output, the absolute amount of software produced increases so much that the actual number of software engineers employed remains constant. As long as engineers, or humans generally, retain some relative advantage to AI, then there is no economic incentive toward full automation, and the labor market could remain steady.

I fear the bull case may prove to be technically true and substantively false.

Firstly, there is an inherent lag between the release of a new model, subsequent development of new automation techniques, and identification of the new optima. The continued rapid pace of change and various incentives to manage costs mean that many (most) companies will over- or underestimate the amount of labor and capital investment necessary to reach the optimal labor-capital split for a given level of model intelligence. An important takeaway from my weeks experimenting with open source libraries and other tools is that it is very unlikely that generic solutions can substitute for a company’s unique needs when working at the frontier of capabilities, as the solutions are incomplete or incorrectly generalized. Even if the initial gains are achieved through Claude Code (rented capital), reaching an optimal labor-capital ratio will require a lot of bespoke development. Executives that fail to understand this problem implement hiring freezes, premature layoffs and generally fail to seize productivity gains—or its opposite, with excess investment in AI automation and failure to reallocate labor according to the comparative advantage of humans relative to AI.

I am particularly concerned that most executives will interpret AI as an opportunity to shift resourcing away from engineering toward traditional business functions like finance, marketing, etc., when the most efficient use of labor may actually be to have engineering automate internal business processes and move many traditional roles toward new, AI-enhanced positions.

The second risk I see is the loss of marginal utility of software. It may be that we have a near infinite number of processes to automate, so the long term risk is small. But, as with the efficient allocation of labor, the real bottleneck is our own ability to identify new applications of software as marginal costs drop and capabilities increase. Up until now, it seems to me we have seen very few practical innovations using generative AI capabilities outside the model’s own chat interfaces and software development. While these advances alone are huge, it demonstrates that we are already struggling today to invent products on top of the current frontier, let alone the frontier of tomorrow.

The third problem, and the most profound for our lifetimes, is that we have no guarantee that humans will retain any comparative advantage over AI. It is of course comforting to cling to this idea, and we could feasibly retain important comparative advantages for years and years to come. But if we extrapolate into the coming decades, I would anticipate we reach a point where humans have no meaningful comparative advantage over AI and are no longer needed in the production of software or any other asset.

I Love my Claude, I Named Him Bob

The history of cloud computing is sometimes discussed by the zoological terms we used along the way.

Servers were once like pets. They had names and you managed the lifecycle of a server very carefully. If your server died, it was very sad, and you probably had a funeral or maybe you were fired. Eventually, though, we got good at virtual machines. Virtual machines allowed us to create and destroy servers as a semi-regular part of operations, and it was often convenient to have a lot of them, so we started to think of servers like cattle or herds. Over time we got really good at managing lots of virtual machines, so we ended up with swarm models, where our “servers” were so lightweight and temporal they resembled insects more than cattle. Eventually this proceeded so far that we no longer need to think about servers at all. In today’s serverless models, compute is microbial; “servers” appear and disappear without any human intervention.

When I sat down to write this post, I assumed automation of software production would require agents to follow a similar evolution, with human attention spread across greater and greater numbers of agentic coding sessions, each tackling an independent workstream. In this model, our Claude Code sessions are still pets. We manage each session’s development cycle, we ensure they run in an independent directory, we carefully track context, etc. Even if we run several concurrent sessions, we still tend to each directly.

I’ve become skeptical that agentic development will follow the same taxonomy from pets to herds to germs.

The past weeks’ exploration of orchestration models demonstrate a belief that current model intelligence already allows for a “herd” model. Today’s orchestration tools can already produce working software, and it’s clear to me that Anthropic will continue to add features here. I think a full herd-model of agentic development would have to mean that multiple independent agents can handle complex or multi-phase workstreams, either coordinating with each other or under supervision of an orchestrator, without requiring human intervention on the individual sessions, while still soliciting human feedback on individual pull-requests as an optional feedback mechanism for the ongoing development.

But I worry this entire line of thinking is ultimately an attempt to build our way past the limitations of today’s model intelligence. Until agents adhere better to instructions and design principles, I don’t believe much more automation is possible, no matter how cleverly we orchestrate. Orchestration is a strategy that seems to make sense today, to better manage context windows, to parallelize work, to self-correct when Claude gets stuck or introduces bugs, etc. These are workarounds for the problems of Opus 4.5. Will Opus 5.0 or 6.0 or whatever require the same strategies? It seems likely we’ll continue to need an equivalent to subagents for context management and parallelization. Beyond that I’m unsure. Are we only anthropomorphizing AI, assuming that it will work better as a team, just as humans do? Will tomorrow’s models easily hold an entire backlog’s worth of requirements in theirs “heads,” chomping through features one-by-on?

That does not mean that new techniques, including orchestration, can’t already improve on your productivity. In my earlier chart, I’ve placed the current optimal capital-labor split at 40-60. How many companies produce the same amount of software as in 2023 with 60% of the team size, at 85% of the cost? Or 40% of the team size at equivalent costs? My guess is already very ambitious! It’s possible a mature version of gas town could still expedite development, even if significant human supervision and intervention is required. I am only skeptical these approaches can take us beyond those ratios, or that they will still apply as model intelligence improves.

I have the impression that some engineers think the fault is themselves—that if they could only find the perfect workflow, or write the perfect library, or spend a few million more tokens every month, they could finally automate 100% of software production. But the capabilities just aren’t there. You can’t automate yourself out of a job quite yet.

I am not actually going to write a post about Nebraska or turtles, at least not yet

I know you were looking forward to ongoing comparisons with looms and steam engines, but I know more about cloud technology than the Industrial Revolution.

Pun intended

Interesting post, thanks for sharing it on ACX Classifieds.

I ran it through a couple of the skills in my reasoning skills library. In particular, handlize (search a text for reusable concepts) and rhetoricize (filter a text for facts, then rephrase the facts in several different emotional valences).

https://claude.ai/share/2ce86dad-003a-4b9c-a8ff-75736f0d490a

###### CLAUDE ######

original emotional center: “the hype is overblown; automation has real limits today; you probably can’t automate yourself out of a job yet, but the long-term trajectory is uncertain and possibly grim.”

transformed emotional center (b1): “the tools are converging on something real; the limits are parameters, not walls; the trajectory is tractable if you treat checkpoint frequency as a design variable.”

Strong analysis of teh labor-capital tradeoff in agentic dev. The compounding error problem (5% drift per changeset) is spot-on and something I ran into building a multi-agent pipeline last month. Wihtout tight feedback loops, technical debt spirals fast even with good models. The pet-to-cattle analogy breaks down here bcause unlike VMs, agents need continuous human oversight at current intelligence levels.